Last week, excerpts from an open letter by Pakhshan Azizi, a Kurdish political prisoner sentenced to death, titled “Concealment of Truth and Its Alternative,” were circulated on social media. The following text is a translation of the complete version of Pakhshan Azizi’s letter published by Bidarzani on 27 July, 2024. In her letter, Azizi details the violent manner in which she and her family were arrested by security forces, the torture she endured during her detention, and her political stances and activities.

Concealment and Unconcealment of Truth

She pressed her hands against the walls of her womb to keep from falling, resisting the abortion drugs. From childhood, she was guided by the voice of a suffering mother who taught her the lessons of resistance and life, she learned how to endure.

«بۆیەت دەبەستم تا خووی پێ بگری، نەک تا من ماوم لە بەندا بمری».

“I tie you up so you can get used to it, so that as long as I live, you won’t perish in captivity.”

Between life and time, a war is unfolding!

She pressed her hands against the cell wall to avoid falling. Time had dissolved into an endless twilight, where day and night were indistinguishable. She wandered through this perpetual dusk, seeking a way to exist beyond mere survival, to grasp the essence of true being. With the government’s methods of intimidation and twenty guns aimed at her, she was branded a terrorist—an ironic label that captured the very essence of the public fear she was forced to endure.

A seventeen-year-old boy, reunited with his aunt after years apart, along with his father, sister, and brother-in-law, lay sprawled upon the ground. Their hands were bound behind them, guns menacingly aimed at their heads. This so-called ‘sacred family’—the very cornerstone upon which the Islamic Republic’s foundation was built—was shackled and forced to the ground. A cruel smile of triumph, emblematic of the ‘state family’s’ power, marked the operation as a success.

They move upwards and higher…

Scenes of massacres and destruction of thousands of Kurdish-Syrian (Rojavan) families played like a tragic movie before her eyes.

In extreme physical weakness, she clung to the walls of cell 33 in Evin, the very cell where, in 2009, she was detained under the same charges of ‘being Kurdish’ and ‘being a woman,’ and striving for ‘xwebûn’ (being oneself). From cell 4, she can hear the sound of her father’s coughs; he has suffered three strokes; due to cancer, recently underwent surgery, and whose body still bears the scars of bullets from the 1980s. And from other cells, she hears the cries of a sister who repeatedly begs to see her only child, who is terrified.

On the first day of interrogation, they offered to settle the case quietly without going to court!

She was hanged several times during the interrogation, buried ten meters underground, and brought out again, considering her disillusionment and brokenness!

Historical memory is filled with these events—a deep understanding born not from estrangement, but from a lifetime in Kurdistan since childhood. From childhood, she was labelled a separatist and a member of the second sex, never recognized as a proper citizen. She faced a choice: either refute these labels by aligning with ‘the other’—a boundary that had already defined her—or strive nobly in service to her people. Yes, for the central authority, the Kurds are insignificant, count for nothing, but for their sentences, they bear the heaviest and greatest weight.

The nation-statist mindset has not shied away from employing the most violent methods for its own survival, thereby perpetuating a cycle of authority and violence.

Boundless Orientalism manifests as a centralist and authoritarian ethos, drawing stark lines between self and other. Unhesitatingly, it wields politics and violence to marginalize and essentialize structures.

Engaging with social realities in a material and objective manner—rather than realistically—renders those truths historically concealed by erasure policies. This approach aligns with positivist science, distinct from the more intricate field of sociology. It unequivocally entails adopting and implementing strategies characteristic of capitalist modernity, rather than those of anti-capitalism.

Utilizing the strategy of capitalist modernity within the Middle East, external forces have fragmented the territorial body and essential cultural integrity of Kurdistan, thereby branding the Kurds with a stigma of separatism since their inception. Kurdistan represents a dynamic society that has historically resisted subjugation by any state. A pivotal distinction in contemporary Kurdish society lies in its evolutionary shift from nationalism towards the establishment of a socialist community.

Not through concealment or hostility, but by respecting all beliefs…

Addressing separatism necessitates the establishment of a statutory guarantee—one that often unjustly stigmatizes Kurdish individuals as separatists.

Once again, during her interrogation, her disillusionment and brokenness are pointed out to her.

The scenario unfolds as a tragicomic drama involving pragmatist and positivist actors who are nourished daily on capitalist modernity through their policy implementations. The core issue here is identity rather than security. In situations where national security is emphasized, concerns related to identity and societal safety are systematically undermined and neglected. Moreover, the individuals responsible for addressing these issues often face deep-seated personal dilemmas, causing them to personalize the broader problems, thereby intensifying the crisis to its zenith.

A human being is defined by their gender (the first dimension of perception), their language, culture, art, management, freedom, way of life, and overall ideology. When any of these dimensions of life are aborted or cut off, there is no room left for a human life. If you abort a woman’s will, as a dignified human being, there is no longer any room for a free life. This signifies a decline in human-ethical-political standards, where life, devoid of its own identity, becomes defensive, and enters into a stage of rebellion.

Insults, humiliations, and threats fill the room, exacerbated by the worst psychological and physical conditions resulting from a prolonged hunger strike, where the pressures of identity and history come to rest. Months of silence break into a defiant shout: I am not a terrorist. The interrogator’s clenched fists asserting his authority as a statesman each time. His roar becomes a scream: ‘Why do you conceal the truth?!’

You have concealed the most profound social truth: the essence of womanhood, her identity, her Kurdishness, her life, and her freedom. What truth and what concealment are you talking about?!

Concealment, erasure, assimilation—these are the systematic edicts that sow the deepest social harms and frame the pursuit of truth as defiance against the state and conflict with others. These very policies perpetuate a relentless cycle of interrogation, whirling in a ceaseless and vain loop.

Being indebted to the people and engaging in social and ethical services outside the confines of the nation-state are criminalized and subjected to the creation of manipulative scenarios, with frequent threats of alternative scenarios to undermine social trust. It is overlooked that democratizing a society happens beyond the nation-state’s borders, and constructing an ethical-political society involves actively refining and perfecting the state’s flawed policies.

Authoritarianism, sexism, and religious extremism are the root causes of social, political, economic, and cultural crises. Therefore, these causes cannot be the solution. It is the people themselves who possess the social and political consciousness and will needed to overcome these crises. Concealing the truth about women, Kurds, and all marginalized communities, along with succumbing to historical distortions, represents the greatest concealment of truth.

It’s a historical concealment, not a solution. Even in defining the problem, you face an issue, and in presenting a solution, you are helpless.

It’s not just the Kurds who face issues; there is a broader ongoing reality. The core of the problem has become obscured, rendering any investigation or scrutiny effectively meaningless. Analyzing social realities demands approaches that are more scientific, philosophical, realistic, and sociological. Strategies that more accurately reflect the truth must be embraced. Merely addressing problems superficially, rather than resolving them authentically, can never provide a real solution. Destroying the potential of women and marginalized communities out of fear and intimidation is unacceptable. Democracy and politics should never fear challenging social realities that have a strong historical memory of genocide, denial, and annihilation.

True politics manifests only when those traditionally marginalized become active participants. It embodies the empowerment of the dispossessed, those presumed unfit for political engagement, who begin to address societal concerns—this realm is neither one of fear nor threat. They demonstrate decisiveness and capability. Sovereign rhetoric should inspire a quest for truth and the forging of will. Dictating the direction of travel and the traveller’s identity in accordance with centralized power does not constitute democracy; it represents a fundamental breach of democratic principles. Justice is not served by enforcing laws that are themselves the roots of crisis. True justice involves assigning merits based on rightful identity. If the same authorities that inflict death, poverty, exploitation, arrogance, and hypocrisy also administer punishment, can we legitimately claim that justice has been achieved and truth articulated? What significance can such a claim hold when truth itself is systematically concealed? The difference between ‘centre’ (مركز) and ‘periphery’ (مرز) lies in a single letter (ك). This letter symbolizes the concealment of truth, which is rooted in the centre itself.

She has been in solitary confinement for months, deprived of books, contacts, and visits. Suffering from frequent bleeding and enduring constant hunger strikes, her health has reached a critical condition. She undergoes relentless interrogations, coerced into confessing to things she did not do. Is there anything else to do besides draining one’s strength to extract information. She repeats aloud to herself that she is a small drop in a vast ocean whose flow is inevitable.

She massages her legs to be able to stand. She rises, then falls. Over these five months, she has repeatedly ventured to the brink of non-existence. This is not unpredictable; we’ve embarked on this journey with these ups and downs. This is the meaning of our lives: the pain that doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. Since childhood, and even more pronouncedly now, we have lived on the edge, our lives shaped by childhood stories, poems, and songs—navigating betrayal and heroism, love and hate, death and life in unique ways. We have felt and lived the essence of life on the edge of existence and non-existence with all our being.

We are born condemned. Our entire lives must be a relentless quest to prove our worth. We may not yet be ourselves, yet we must strive to be ourselves.

The smell of burning and blood has engulfed the entire Middle East. Each instance brings another haunting memory to her mind. The first corpse she saw was at the age of 18, when Khadijah, burned from head to toe by her husband and brother-in-law, with her hands bound, had her life set ablaze. These true stories are endless. She has encountered dozens of other social harms through her work and in university, depicting the dire state of society. She remembers the dozens of women and children who, during ISIS attacks, saw their husbands, brothers, and fathers beheaded before their eyes. She recalls the girls who were captured, repeatedly raped, and some who set themselves on fire.

Mothers holding their infants as their milk dried up, and barefoot children—hundreds of whom lay on the stoning rocks, becoming desiccated. Dozens of female fighters whose bodies were burned and dismembered by Turkish airstrikes on one side and ISIS attacks on the other. Fighters who sacrificed themselves for the Khadijahs, the children, and the grieving mothers.

She wakes up abruptly, unable to rise, and starts vomiting—a purge of historical trauma.

In the Middle East, the crisis has transcended tragic dimensions, profoundly destabilizing the entire social fabric. The region has been plunged into turmoil by the implementation of modern, capitalist strategies, orientalist perspectives, and flawed policies that are aligned with global strategic interests. These factors have collectively resulted in extensive devastation and widespread bloodshed.

Forced to sit down, the threats and humiliations resume. Her hands bore deep scars from the war. “Why did you go to Syria for ten years? Why didn’t you go to Europe?”

At the heart of the question, the pull and attraction of Europe and the West can be deeply felt. It was as if they were speaking of their dreams or pushing you toward what they opposed! Where we are, we do not belong, and when we leave, we must find our place!

After the disappointment and failure of the 2009 case, which you claim as a victory, she served humanity beyond the artificial borders, and you remained the same interrogator from 2009 who couldn’t even become a soldier. Due to the lack of a healthy socio-political atmosphere, she distanced herself from her country. Life had lost its meaning. She moved to a place that also belonged to her (as you had said, Syrian Kurdistan is ours, as is Turkish and Iraqi Kurdistan). So, she didn’t go anywhere outside of what was rightfully hers. Of course, if it’s yours, not hers?! Another place in the Middle East where a revolution is taking place. Dreams cannot be killed. An alternative and democratic system reached its peak with the century’s resistance of Kobani (which, of course, was not a one-sided struggle but an ideological one) and became a turning point for the entire region and the world. The beginning of a new chapter of democratization.

Despite all the pain and hardships, working in refugee camps was the greatest moral and ethical contribution to a community she could think of that has long suffered under oppression. Performing such humanitarian work, which becomes revolutionary by crossing borders, were you there as well?

The voice rises: is everyone there a member of the PKK?!

This implies that there are millions of PKK supporters. But what constitutes a group? It is the adherence to the philosophy of Apo, the leader who, as a sociologist, has provided profound analyses of the Middle East and Kurdistan. Despite being held in solitary confinement in Imrali for 25 years following the international conspiracy of 1999, she has chosen to adopt cooperative methods beyond the nation-state system, considering this an honour. Your definition of the problem is fundamentally flawed.

The belief in initiating a revolution with a transformative mindset, followed by structural changes, is a fundamental principle of modern revolutions.

Within a revolution, naturally, one’s character is formed and shaped. Betrayal and heroism become more pronounced as they are tested within the context of social and political responsibilities. When you deeply engage with social issues and closely observe the current environment and the urgent need for organizing and mobilizing the populace, you come to understand the importance of systematic approaches and the reconstruction of a moral-political society amidst conflict. Iran itself fought against ISIS in this context. Through this experience, you learn practical and highly effective solutions. Until democratic modernity is established, it is impossible to escape the interference and intervention of capitalist modernity in the region. The Middle East must reclaim its fundamental role in the social process.

In the modern history of a democratic Middle East, the forces of the nation-state and the mechanisms of democratic governance operate together in a dialectical relationship. Understanding this dynamic requires accepting local differences, yet this does not equate to separatism! In Syria, for instance, democratic and revolutionary popular forces possessed the capacity to overthrow the government, but chose instead to establish their own system, thereby diminishing Assad’s central authority. The revolutionary system progresses on its own path. Democratizing society involves democratizing the family to overcome gender biases, democratizing religion to move beyond religious dogmatism (not religious hostility), and democratizing all existing institutions to prevent authoritarianism. This forms a common theoretical framework that avoids falling into dictatorship and purging the authentic traditions of the region’s peoples, which are a significant part of their identity and existence.

All her activities and efforts have been in the aim of serving and fulfilling her historical duty towards her lived experiences and historical oppressions. She firmly believes that the right way to achieve a democratic society is through a democratic approach to building an ethical-political society where people deliberate on social issues, make them their concerns, and find solutions. This is the essence of democracy.

Democratic self-governance, guided by the paradigm of a democratic nation (inclusive of all ethnicities within its borders), aims to address the profound crisis in the Middle East. This approach emphasizes organizing the populace through the principles of the sociology of freedom and the application of Jineolojî in its policies.

Disciplines involving deep historical, social, and political analysis provide solutions that empower people to rise and address issues and crises themselves. They establish grassroots committees for peace, economy, education, services, health, culture and arts, religion and belief, youth, and women. These committees resolve hundreds of issues daily, even under the most critical wartime conditions. Men and women, working together in free coexistence and shared leadership, rebuilding a society shattered and engulfed in crisis, imbuing life with new meaning—a life that has been stripped of its essence. There is a firm belief and unwavering faith that they are on the path to freedom. Despite all the hardships and suffering of the ideological revolution, they experience freedom moment to moment. This vision does not differentiate between Syria, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Afghanistan, and other regional countries, or Gaza, which has faced genocide and the bloodshed of thousands (from West to East). This is the essence of freedom.

And those who have embarked on the path of truth and freedom have redefined the meaning of both life and death. It is not death that we fear, but rather a life devoid of honour and marked by servitude. A truly free life begins when women—the earliest of the colonized—live with steadfast resolve for their dignity and honour, embracing death in the pursuit of living freely.

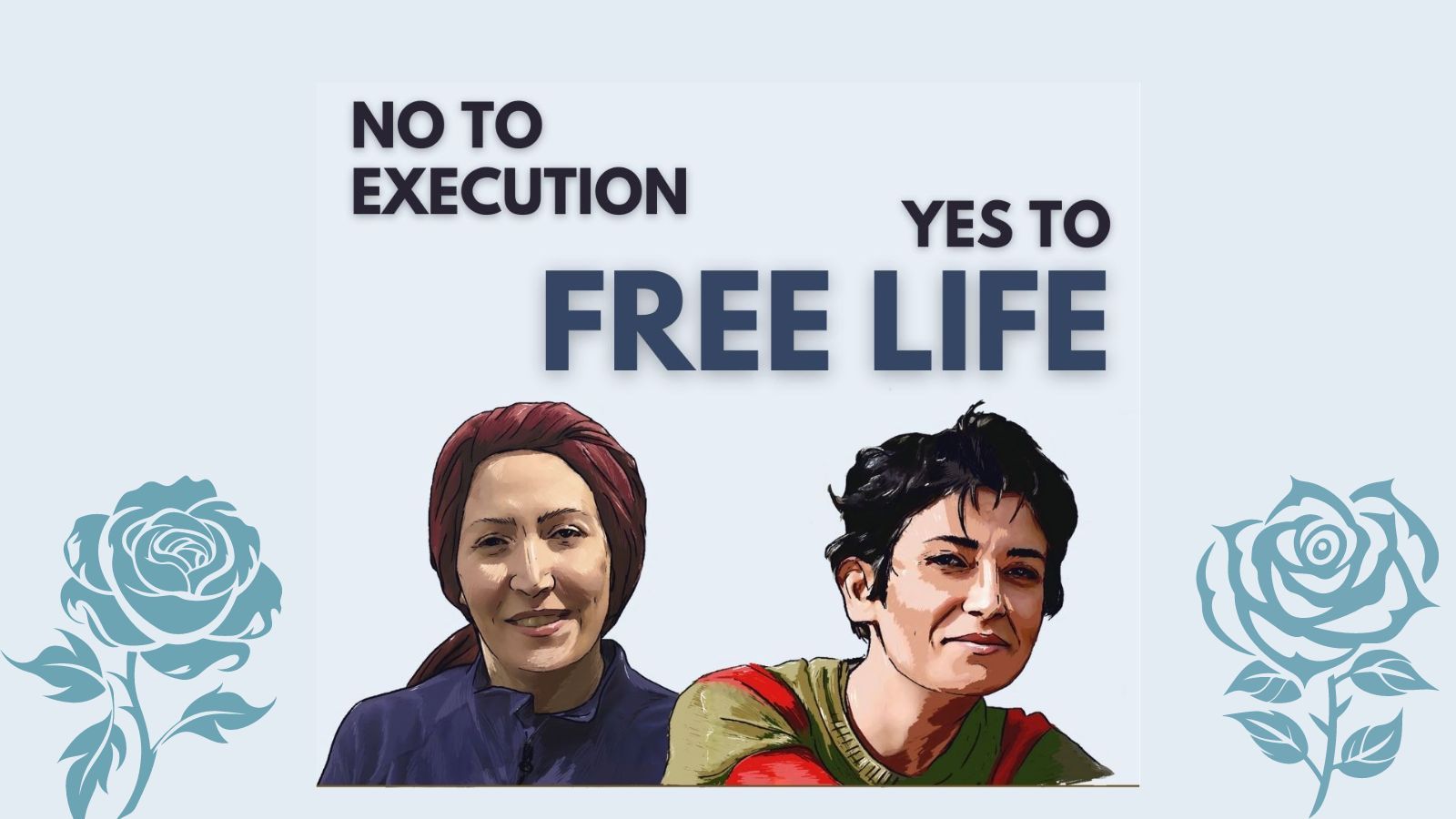

Neither Sharifeh Mohammadi nor I, along with the other women on death row, are the first or the last to be condemned solely for seeking a free and honourable life. However, without sacrifice, freedom cannot be realized. The cost of freedom is substantial. Our crime is linking Jin and Jiyan to Azadi (Women and Life to Freedom).

I am her. She is me. But I am a mere drop in the ocean. You are the ocean. Our flow is inevitable. We are unconcealed.

Pakhshan Azizi July 2024, Evin Prison

Sharifeh Mohammadi, a former member of the ‘Coordination Committee for the Formation of Workers’ Organisations', was arrested in December and sentenced to death on 4 July by the Rasht Revolutionary Court on charges of “baghi” (armed insurrection). Pakhshan Azizi, a Kurdish journalist, social worker and political prisoner, has been imprisoned in Evin prison for the past year. She was sentenced to death on 21 July by Iman Afshari, a judge of Section 26 of the Revolutionary Court. Both were subjected to severe torture and inhuman treatment during weeks of detention.