In recent weeks, Western media attention has been fixated on the disappearance of a submarine, named Titan, which was on an expedition to explore the wreckage of the Titanic. The submarine had embarked on a deep-sea voyage, offering an exciting experience to a small group of affluent tourists who each paid $250,000 USD to attend. Among the five passengers on board were British billionaire Hamish Harding, business magnate Shahzada Dawood and his son, a renowned French oceanographer, and the CEO of OceanGate, the company organizing the expedition.

Following the distress calls, officials swiftly launched a multinational search and rescue (SAR) mission. The joint efforts of the U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards, along with numerous private and commercial vessels and aircraft, were complemented by the deployment of international teams with highly specialized SAR technology. The Royal Canadian Air Force deployed aircraft equipped with advanced sub-surface acoustic detection technology to aid in search efforts, while a French research vessel with an unmanned robot capable of scouring the depths of the ocean floor also joined the operation. Within five days, the search teams located numerous parts of the submerged vessel, prompting an investigation into the cause of the submarine’s implosion and the fatalities on board.

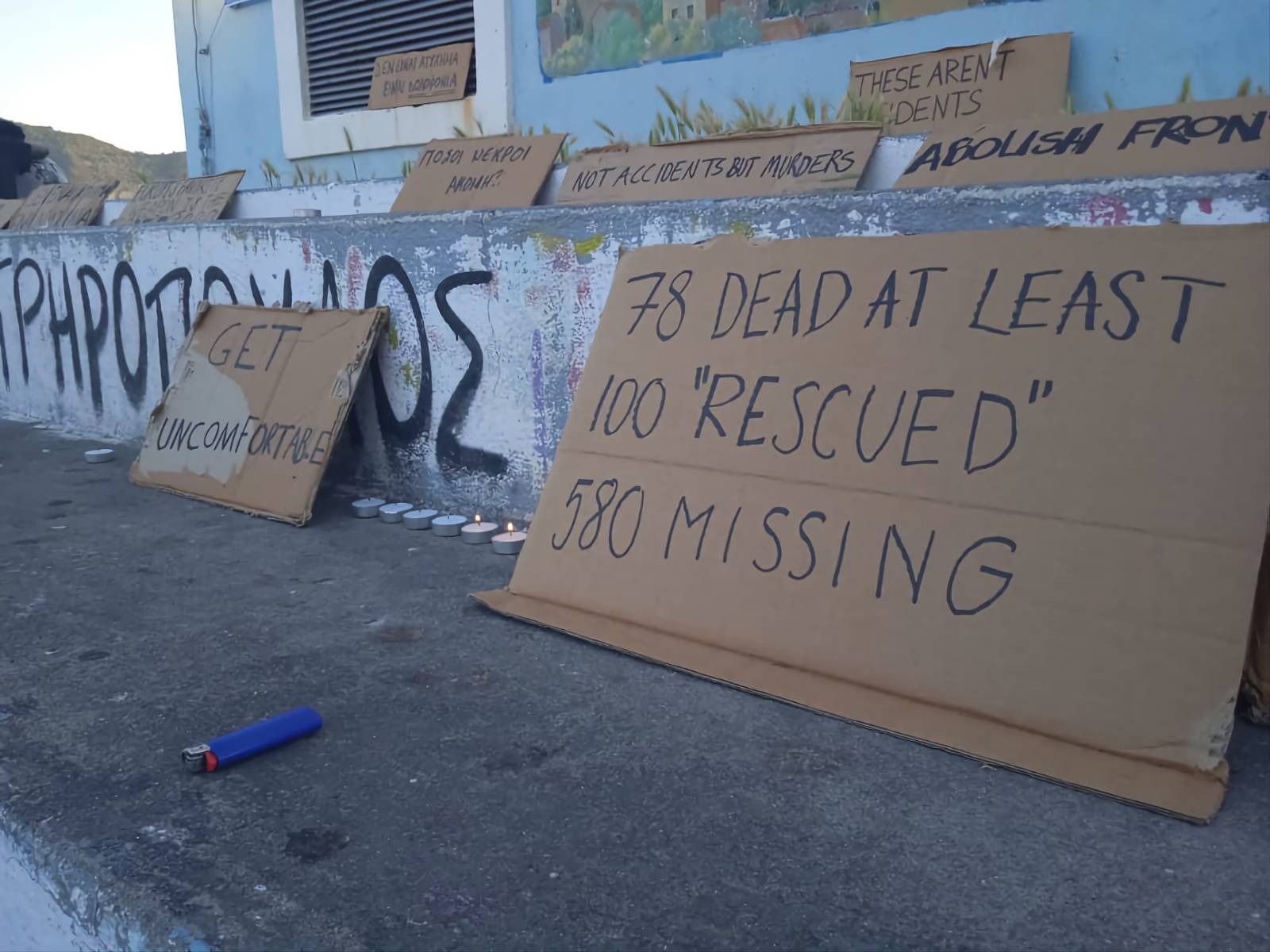

While the media extensively covered the full-scale SAR operation for the submarine and its passengers, recent events have once again exposed a disturbing disparity in the value placed on human lives. Just before the Titan incident, a vessel carrying approximately 750 asylum seekers, including over 100 children, en route from Libya to Italy, capsized in the Mediterranean Sea. Despite claims by the Greek Coast Guard that the vessel declined assistance, activists argue that those onboard had been calling for help for up to 15 hours, which went unanswered. Further investigations by journalists supported activists’ claims and indicated that the vessel had displayed minimal movement for at least seven hours before it eventually sunk. On June 23rd, the same day when the remnants of the Titan ship were recovered, another tragic shipwreck unfolded at Europe’s external borders, approximately 160 kilometers southeast of Gran Canaria. It is presumed that 39 individuals lost their lives during this attempted journey from Morocco to Spain. Again, despite waiting for more than 12 hours for assistance, the distressed vessel received no help from Spanish or Moroccan authorities or interest from the international community or media.

These events, although distinct, form a poignant but predictable backdrop for recent developments in a new ‘European asylum and migration policy’. After years of negotiations, at the beginning of June, the European Union (EU) achieved a compromise agreement on substantial reforms to its asylum system, heralded by politicians as a “historic” approach. However, the proposed Common European Asylum System (CEAS) is not a departure from the EU’s previous actions but rather an extension of policies pursued by different political factions, including both right-wing and social democratic groups, over several decades.

A crucial aspect of the CEAS is its commitment to further expanding funding for the EU’s ‘border externalization’ agenda. Externalisation policies involve outsourcing border control and ‘’migration management’’ to non-EU countries, often with the objective of preventing the arrival of asylum seekers at EU borders. In this process, so-called non-EU partner countries receive financial assistance, training, and technical support to strengthen their ability to control migration in the economic interests of the EU. Additionally, bilateral, or regional agreements are formed to promote collaboration in border management, migration control, and the deportation of migrants to their countries of origin. Since reaching the agreement on the CEAS, the EU wasted no time in initiating a new border externalisation regime deal with Tunisia, offering the country €105 million for border management, search and rescue, anti-smuggling, and return efforts. Despite Europe’s ongoing criticism of democratic backsliding in the country since President Kais Saïed assumed office in 2019, along with his incitement of racist and anti-immigrant sentiments that led to an upsurge of brutal violence against asylum seekers throughout Tunisia in February 2023, the EU remains committed to offering an additional 1bn financial assistance contingent upon Tunisia’s implementation of necessary reforms – the underlying objective is to exert control over migration from Tunisia by striking a deal with the president.

In addition to externalization projects, the CEAS also encompasses various new measures, including imposing charges of €20,000 per person on member countries that refuse to host refugees, and the implementation of a new system facilitating the redistribution of migrants across EU nations, with specific quotas for frontline states like Italy, Greece, and Spain. Additionally, each member state is allowed to determine its own interpretation of what constitutes a “safe” third country for deportations, which raises questions about the protection of asylum seekers and the potential for disparate treatment among EU states. The CEAS also involves the outsourcing of asylum procedures to the EU’s external borders and a proposal of prompt deportations of anyone who is not granted asylum.

The ratification of the current version of the CEAS regulation would present a relinquishment of the fundamental right to asylum as outlined in the 1967 Protocol to the 1951 Geneva Convention across the European Union. However, it is essential to consider this development within its historical context, taking into account the EU’s decades-long border and migration policy trajectory. Since the establishment of the EU which coincided with the onset of globalization, there has been a notable emphasis on facilitating the movement of goods, information, and money across borders through trade agreements and technological advancements. In contrast, the mobility of people has faced increasing restrictions and control, with intensified investments in border security and surveillance systems. In 1992, when the EU implemented liberalization measures and free movement within its internal borders, it concurrently implemented heightened security measures at its external borders due to perceived threats associated with the collapse of real socialism and the stigmatization of migrants arriving from the East as a dangerous “other.” These measures were further amplified in response to the US-led “global war on terror,” which erroneously conflated migration with terrorism, thereby providing justification for the implementation of exceptional security measures to address it. In both instances, the groundless notion of a “migrant threat” was deliberately manufactured to legitimize the implementation of stringent security measures within the EU, resulting in unequal and tightly controlled movement across its borders for non-citizens. The primary objective of these measures has been to manage a highly expendable and exploitable global workforce of migrants according to market demands.

Another important point to note is that while the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) carries the risk of eradicating individual asylum assessments and foreshadows even more extreme securitized solutions, it also represents a return to the original framework of international refugee law as outlined in the 1951 Geneva Convention. Initially developed to address the needs of European refugees in the aftermath of World War II, the convention gained universal applicability only through the 1967 Protocol. The proposed CEAS indicates that the EU’s asylum policy continues to be guided by Eurocentric and exclusionary principles rather than ones of internationalism or universality. This has become increasingly apparent through the contrasting treatment of European and non-European refugees, notably the preferential treatment extended to Ukrainian refugees in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion in 2022 compared to those arriving from countries outside of Europe that are not predominantly white and Christian.

Fueling a border security Industry

Discussions and concerns surrounding the adoption of the CEAS fail to acknowledge a critical aspect: its implementation is not a shocking or unprecedented development, but rather a continuation of the EU’s long-standing and widely supported agenda of migration control. This agenda has already led to the establishment of an extensive transnational security and surveillance system that extends well beyond the borders of the European Union. Over the course of three decades, this coordinated apparatus has experienced significant expansion as a direct result of the enduring policies that receive overwhelming consensus from all sides of the political spectrum. Now, with the proposed CEAS, these efforts will be further reinforced. This will entail further funding allocated towards militarizing borders, developing border infrastructure, providing police aid, deploying advanced surveillance technologies, and establishing transnational police collaborations in targeted third countries. All of these efforts are aimed at controlling migration to serve the interests of EU markets and capital, with the normalization of border deaths an unfortunate but necessary consequence.

The externalization of EU border policies, primarily executed through development assistance funding schemes, has played a vital role in fueling a broader border-security industry. This industry involves a network of actors, encompassing both state and non-state entities, local political elites, private actors, NGOs, think tanks and others. Each of these actors benefits in various ways from the expansion of the industry. Its ultimate objective is to manage and control migration in alignment with the political and economic interests of the EU by implementing border security projects in third countries. The introduction of CEAS represents yet another step towards further expanding the influence and operations of this industry. The border security market is experiencing significant growth, with an estimated annual expansion of 7.2% to 8.6%, projected to reach $65-68 billion by 2025. Europe, in particular, stands out with an anticipated annual growth rate of 15%, especially in the biometrics and artificial intelligence (AI) sectors. Notably, European, Australian, American, and Israeli arms companies have been identified as the major beneficiaries of this industry’s growth and expansion. In this sense, it is crucial to note that the EU’s externalization policies are not only being shaped by market needs, in terms of acquiring skilled and unskilled migrant workers, but also by actors which stand to profit from the industry’s expansion and the further investment in border security.

The significant increase in EU investment in border externalization has led to the emergence of non-state actors, including semi-public companies and international organizations specializing in consultancy, training, and management of border security projects in non-EU countries. These non-state actors have thrived due to the industry’s growth and have played a significant role in shaping EU externalization efforts. Prominent among these actors are the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex). All three organizations are involved in implementing border control projects on the ground, such as training border guards, conducting deportations, establishing international police cooperation networks between EU member states and third countries, and procuring surveillance technologies and police equipment for law enforcement agencies. With their budgets having expanded exponentially over the last ten years, the new CEAS promises to bring further benefits to these organizations.

What often goes unnoticed, however, is that organizations such as IOM, ICMPD, and Frontex not only contribute to the practical implementation of EU’s border externalization policies, but they also play a crucial role in establishing a coherent and internationally accepted ‘truth regime’ on migration, through the production and dissemination of knowledge and information – which is often framed in the language of human rights and humanitarianism. This is particularly important because, in the absence of international agreements or laws governing mobility across borders, the colonization of discourses becomes critical for the legitimation of violent border policies.

These organizations engage in a variety of activities, including publishing reports and statistics, investing resources in public relations, training journalists in the Global South, creating migration glossaries, running media academies, funding academic research, maintaining academic journals, and participating in informal dialogues with stakeholders from industry, state, and non-state sectors. Scholars, journalists, policymakers, and activists working on migration issues commonly depend on the data produced by these organizations, notably the IOM, which positions itself as a UN agency despite its lack of a human rights-based protection mandate and notable shortcomings in terms of accountability and transparency. Migration statistics these organizations produce, in particular, are perceived as possessing significant scientific credibility. However, it is important to acknowledge that the data produced is not inherently objective or unbiased; it is shaped by choices regarding data collection methods, categories, indicators, and units of measurement. As such, statistics do not simply reflect an existing reality; they actively shape and reinforce it. Additionally, IOM, ICMPD, and Frontex have a vested financial interest in producing data and knowledge that substantiates and justifies the EU’s externalization agenda, as outlined in the CEAS. This further solidifies their expertise in implementing border externalization policies and contributes to the continuous growth of the border security industry, guaranteeing their own relevance and ongoing funding.

Given the current realities, it is crucial to develop counterstrategies and adopt a new language to effectively address the complexities of borders and migration. This discourse must move beyond the legalistic framework of human rights and international law, which not only lacks relevance, but is now also being manipulated by profiteers to justify the expansion of the border security industry. To confront this, a fresh approach is needed—one that can successfully challenge the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), resist co-optation by the (neo)liberal agenda, and can clearly address the issue of unequal mobility and exploitation. This strategy should not limit itself to questioning the concept of borders and advocating for human rights to be respected; it must also extend its critique to the power dynamics entrenched within nation-states and the overarching capitalist world system, which remains the core driver of these policies. Lastly, it is important to recognize that the current system which gives rise to the need for people to seek asylum cannot (and should not) be relied upon to provide the necessary protections to those seeking it.

Manja Petrovska is a PhD researcher based between Amsterdam and the Balkans, studying the intersections of border control, neocolonialism, and humanitarian imperialism. Her research focuses on the border security industry and the neoliberal rationalities shaping border and migration policies.