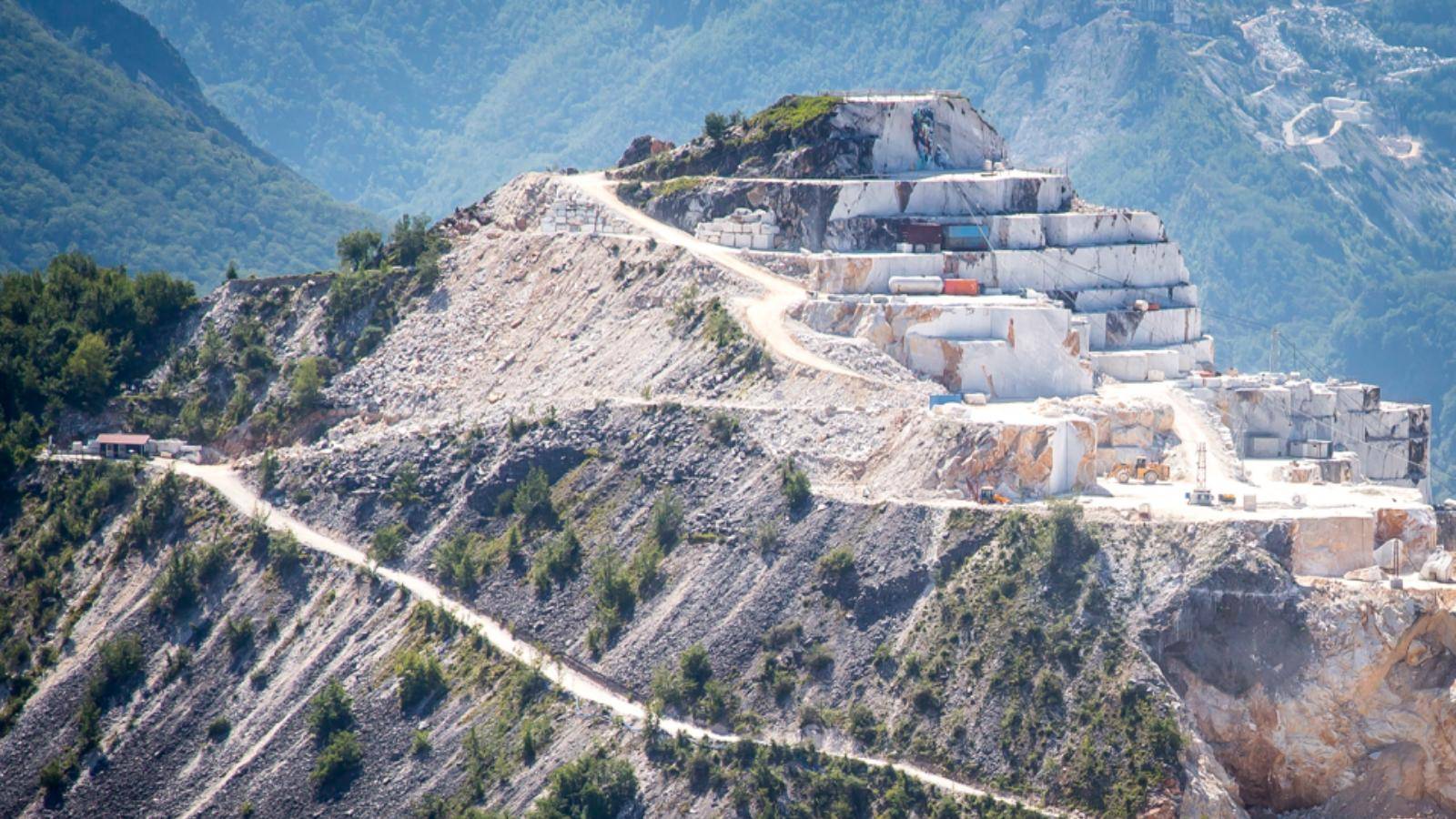

The marble extraction basin of the Province of Massa-Carrara in Italy is known for being a symbol of history, art and culture. It is the place from which Michelangelo obtained the raw material for his statues, in the sixteenth century. But, it is also a place of environmental devastation. The Apuan Alps, where the mining is happening, are hiding one of the longest lived and least discussed stories of extractivism in Italy. The marble industry has had devastating consequences on the unique richness of the Apuan Alps where marble has been mined non-stop since the first century BC. Throughout this entire period the mountains have hosted the most important water basin in Tuscany and an incredible degree of biodiversity. Massa-Carrara is emblematic of how exploitation by human beings is linked to the subordination and subjugation of nature through the ruthless appropriation and exploitation of its resources.

But Massa-Carrara is also a place of historic resistance, of workers and partisan struggles, and today, of ecological struggles against this destruction of nature. In this interview, members of the ecological movement “Athamanta” explain the background of their struggle, the historic roots of marble extraction and how patriarchal myths shaped its identity. They also highlight the importance of bringing together ecological and workers’ movements, and how the perspective of Democratic Confederalism inspires them to strengthen women’s organization, and to fight for a democratic and ecological society.

Can you introduce your collective “Athamanta”?

Athamanta is a floral plant of the Apiaceae family. It is one of the many endemic species that live in these unique alpine territories, set between the sea and the mountains. This flower is the inspiration of our group’s name as we forge a collective path of struggle against the systemic hoarding of the earth’s wealth by large private interests, national or foreign, at the expense of local communities and their territory, that in the province of Massa-Carrara historically takes the form of the extractivism of its famous white marble. Athamanta defines itself as a path of self-training and action that deals with the issue of extractivism in the Apuan territory. Between 2019 and 2020, a renewed ecological consciousness has prompted us to reopen the debate around, what seemed to us, the most obvious contradiction that crosses our territory; the mining practice that has defined the identity of the area for more than 2000 years. At the beginning of 2020, we discovered a huge drawing of Michelangelo’s David painted on the walls of the quarry. This was a blatant instance of art-washing by the quarrying company as they attempted to both valorise the quarry in terms of image and evade the costs of securing the quarry wall, claiming that they did not want to risk damaging the “artwork”. The emerging movement against extractivism then wrote an open letter to the citizens to denounce the great social problems arising from the marble industry and took an action sanctioning David with a banner that says “Devastation is not art”. So Athamanta was born.

What was your main demand when you started your movement, and how did you connect it to other social struggles?

“Stop the devastation in the Apuan Alps and everywhere” was the slogan with which we started the first phase of the movement that corresponded to the need to “deprovincialize” the struggle in the Apuan Alps and get out of the strictly local context. After a few years the process of organization has produced new slogans such as “The mountains do not grow back, we stop extractivism in Apuane and everywhere”. Using the term “extractivism” as a key word has represented a great theoretical and political advance, for the fact of having spread through the struggle a new understanding of reality in the society of Carrara: that extractivism and extractive activity are not the same thing, that extractivism is a capitalist system of devastation of nature and communities based on the principles of industrialism and that the problem is not the mining activity itself, but the capitalist system based on profit.

What is the social impact of industrialism on the community and on the territory?

The first attack is on the level of mentality and imagination. Common phrases such as “Carrara the capital of marble”, “Carrara is marble”, “the heroic craft of the quarry”, “Michelangelo’s quarries” are based mainly on two ideas: that all local jobs depend on the extraction of marble and that the extraction of marble is used for art. As for the first question, although there is a deep conviction that the marble system gives work to the whole city, in reality jobs are decreasing, with less than a thousand jobs upstream and less than three thousand on the floor, compared to a 30% increase in excavation. As for the second argument, the idea of production for art is also a false myth. 80% of the marble extracted everyday ends up in the highly profitable calcium carbonate market, managed by a few large multinational companies such as OMYA.

How do you evaluate the role played by the state in the implementation of the marble industry?

Since Carrara is the epicenter of the marble system, the municipal governments that have followed each other over the years have always focused their policy on quarries under the pressure from industrialists. These policies have led to a progressive emptying of the city: today marble is the most important industrial sector, at the expense of all other productive spheres. At the same time, Carrara is integrated into a globalized industrial market and the percentage of matter that is treated on site is minimal. The extracted blocks go directly to the port and are then processed outside of Italy and the EU where labour is cheaper. The municipal governments do not want to invest in anything else, because in the past it has accumulated debts to build auxiliary infrastructure for the transport of marble, such as large tunnels. This has turned Carrara into one of the poorest municipalities in Italy, despite its great natural wealth. This is a very common pattern in Italy: the procurement system for building infrastructure is one of the sectors with the most important mafia-like alliances between state and capital. In the end, it is the industrialists who created the Marble Foundation who invest industrial profits into essential public works, such as roads and hospitals, that public administrations cannot guarantee, but on an arbitrary basis and not on the basis of the need of the society. This is a real blackmail of the community. With employment levels so low due to relocations, the centre of Carrara is desertifying. New forms of extraction through the tourist industry are emerging as industrialists attempt to enlarge profits, such as sightseeing tours in the mountains to see the caves and associated luxury hotels and restaurants.

Since the marble system, instead of generating wealth for society, produces only profits for industrialists and unemployment for citizens, how are you trying to bring together the ecological struggle and the workers movement?

The central point of this struggle is to avoid potential clashes between environmentalists and workers. This potential conflict is often used as a divisive tool by industrialists to break down social bonds between these groups for their own benefit. Bosses and industrialists often exploit and blackmail workers to shield themselves from the criticisms of environmentalists. We know that we must not fall into this error because the movement against extractivism is developing a new paradigm that sees the only real contradiction as the one between ecology and industrialism. In reference to this, the perspective of Democratic Confederalism was a great inspiration as a model to to build territorial defense movements and democratic social forms that have ecology as a fundamental pillar. Therefore, we started from a strategic alliance that binds the ecological authorities with those of the workers, who are part of the society that lives in Carrara and therefore suffer all the harmful effects of the system for which they work, such as high water bills to compensate for the cost of the purification of rivers. In fact, the processing of marble puts at risk the karst formation of the Apuan Alps, causing interruptions in the aquifers that contribute to feed the large water reserves that these mountains offer us. Byproducts of the quarrying process such as cutting dust and waste oils pollute the already compromised waterways that supply the villages. It is important therefore to understand that workers are not detached from society, are not a class separated from the rest of society, and must assume that the ecological struggles of society are also struggles of the workers. On the other hand, disputes may arise, such as the demand for a reduction in working hours on equal pay, which open up opportunities for solidarity outside the world of work, which can be a key to winning specific union struggles such as turning the workweek of workers into two days of work in the quarry and three days of work to arrange and care for the mountainsides. It is a question of developing a dialectic dynamic of transformation in a more ecological and social sense.

Historically, have there been other resistance movements against the marble system?

Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth century there were 20,000 miners in the quarry who were organised in large struggles characterized by libertarian and anarchist syndicalism. Carrara boasts of being the first place in Europe where workers successfully won the right to a 6-hour workday with travel time included. These great social achievements happened via a well organised large mass labour movement. This phase of the early twentieth century has marked the identity of the quarry and the territory of Carrara as the cradle of Italian anarchism. There is a historical and political link with a very radical ideology of struggle, but today the anarchist identity of the quarrymen is affected by the ideology of industrialism, which is grafted on the historical patriarchal representation of the quarry, and feeds a working ideology among the quarrymen who want to keep their privileges as “working class bourgeoisie” and protect a profitable job from the progressive automation of production, received by a long chain of transmission of the craft from father to son.

Where does this patriarchal image of the quarrymen come from and what is its relationship with the idea of the domination of nature that the quarry activity brings with it?

Marble excavation has been done here for more than two thousand years, since the times of the Romans who first began to dig and bring marble out of the peninsula by sea, through the port of Luni. Over two millennia the work of the quarry has certainly changed, but not so radically as in the last hundred years. The historical imagination views the quarryman as a heroic profession: it is a deeply rooted myth of a man who fights against the mountain, which persists to the present day. In fact, until fifty years ago the extraction and transport of marble downstream was based on methods that were physically exhausting for the workers. It was a very long and dangerous job requiring large amounts of manual labour. It was hard, miserable work with very frequent accidents fuelling the myth of the quarryman as a heroic figure fighting against the mountain for his own survival. Living conditions were also poor with workers often not even returning home during their workweek merely sleeping in shelters near the mining site.

So what role do women play in the struggle?

Marble is a historically male theme: the quarryman is traditionally a man, the hero who sacrifices his life to bring bread home. He is a patriarchal figure, so the woman in this picture does not find her space. As a movement against extractivism we come from a variety of organisational backgrounds, but the perspective of Democratic Confederalism allows us to develop the principle of women’s autonomy. We tried to bring the theme of women’s liberation into the struggle, but in the quarries women are not there and we saw it during the strikes when the relationship between militant women and workers is often complex. Nevertheless, thanks to the autonomous organization in the movement, women are many, aware and proud to embody a strong and self-determined model of womanhood. In fact, the story of the figure of the woman in Apuane should be more investigated because it is a more complex figure than the stereotype of the classical woman. In the common understand women are not viewed as merely submissive figures as there have been important episodes in history in which women have had a vanguard role; such as the revolt of Piazza delle Erbe in Carrara, whose protagonists were exclusively women. It is July 7, 1944, near Carrara passes the Gothic line, the Germans are close to retreating, the tension is very high and the Nazis order the evacuation of the city to prevent it from being liberated by partisans. The women of Carrara gathered under the pretext of the market are secretly organizing themselves: in the market square, on July 7, they spilled their baskets on the ground triggering a riot and starting the city revolt. They were neither runners nor partisans, but women of society tired of the roundups and the Nazi-Fascist presence. This makes it clear that the partisan story is very heartfelt even if it has always been told from the point of view of the male partisan, but the women were much more present, not only as runners or as companions who followed their boyfriends in the mountains, but as guerrillas who took up the rifle and climbed the mountains.

Can you tell us about some other resistance struggle in the Apuan Alps?

Yes, we said that during the Second World War the partisan struggle was very strong because the Gothic line passed through the Apuan Alps. This territory had undergone eight months of raids in retaliation against the large partisan presence that was hampering the retreat of the Nazi-Fascist forces. This story finds parallels with the resistance of the Ligurian-Apuan tribes that faced the Roman advance Northwards towards modern-day France. Repulsed after the first attempts of incursion into the territory, after two hundred years of struggling to defeat the local populations in the mountains the Romans managed to achieve their victory only by clearing a large marshland and the large-scale construction of new infrastructure. Many tribes of the Apuan peoples were deported to the area of Marche and Abruzzo where there are still similarities between the Apuan dialect and the Marche dialect. As you can see, the history of this territory is rich in stories and myths to be rediscovered in opposition to those of capitalist modernity to rediscover an identity of struggle necessary for the construction of an opposition to extractivism for a more ecological, fair and democratic society.